Calvin Tenenhouse and Peter White

December 05, 2022

Are we in a recession? Depends who you ask

In the summer of 2022, we heard lots of lively debate from politicians, industry leaders, and the academic community trying to determine if our economy had fallen into a recession. While recessions often conjure up scary images of food lines and government work programs, we’d remind you that they are a normal part of the business cycle and can often be quite mild. They historically occur every few years and allow speculative excesses to be swept aside, and strong businesses to become more resilient, as they take market share from competitors with poor business models or too much debt.

According to Webster’s definition, a recession is two consecutive quarters of negative gross domestic product (GDP). By that definition the U.S. entered a recession in the summer of 2022, only a short two-and-a-half years since the previous recession in 2020 where more than 24 million Americans lost their jobs in just three weeks (source: New York Times). However, this situation seems different. The unemployment rate is still quite low (3.7%), and businesses are interested in creating almost 11 million more jobs this year — both of which are hardly symptoms of a downturn (Bankrate and AP news). Furthermore, the group of professionals that outlines U.S. business cycles, the National Bureau of Economic Research, uses a different definition “A significant decline in economic activity that is widespread and lasts more than a few months”. So, according to the NBER we are not in a recession. So, who’s right? And why does it matter?

Firstly, it is possible for some consumers and small businesses to feel like they are in a recession even if the broader economy is not showing classic symptoms. In fact, this is a probable scenario as inflation remains near its highest level in forty years. Despite the pay raises that many workers have received, we all still feel like our purchasing power is slowly eroding, resulting in a negative impact on consumer sentiment. The pain is being felt disproportionately by lower-income families, many of whom are coping with the increased price of essentials such as food, gas and shelter. The former is exacerbated by the Fed hiking rates at the fastest pace since 1977, hitting vulnerable North American populations at a time when many were already overextended on home, car, and credit card borrowing. So, how do we know if we are falling into a recession? Below I’ve outlined what metrics myself and the rest of the team focus on to gauge not only the state of the economy, but the possibility of an imminent economic contraction.

- Unemployment Rate – The clearest signal that a recession is underway according to economists would be a steady increase in job losses. In the past, an increase in the unemployment rate of 0.30% over the previous three months has meant that a recession will soon follow (source: AP news). Economists keep tabs on the number of people who apply for unemployment benefits, which indicates whether layoffs are worsening. Currently, applications for aid are at a four-month low. In other words: Fewer employers are resorting to layoffs than we may think from reading headlines.

- Gross Domestic Product (GDP) – After two straight quarterly declines of U.S. GDP at the start of 2022, Q3 saw growth of 6% which is a bullish signal. Canada has enjoyed quarterly growth throughout 2022 as rising oil prices, along with other industrial commodities, made up for weaker growth in other parts of the economy (source: CIBC Economics). GDP is a measure of the monetary value of goods and services that an economy produces and is used to track whether a country’s economy is experiencing growth or contraction. When an economy is growing, as measured by rising GDP, higher corporate earnings and valuations tend to follow suit, leading to healthy positive returns for investors.

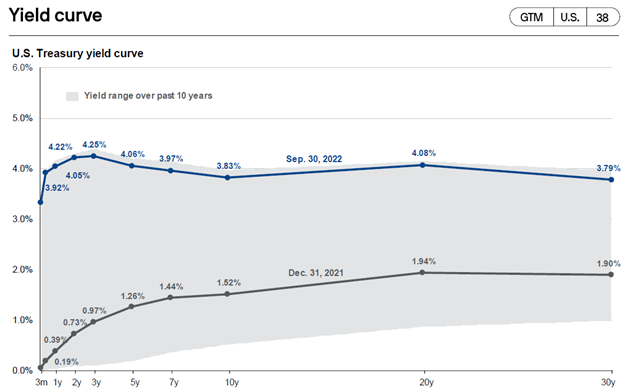

- Treasury Yields – Our team actively monitors changes in yields on different financial instruments for a recession signal known as an “inverted yield curve.” This phenomenon occurs when long-term treasury yields fall below their short-term counterparts. Usually, long-term bonds compensate investors at higher rates in exchange for tying up their money for a longer period, in addition to the uncertainty that comes with the future. Put simply, because I have a better idea of what tomorrow will look like than 2032, I should be compensated more for investing into the 2032 economy (a bird in the hand is better than two in the bush). When bond investors predict a recession that will result in the Fed cutting rates in the future, long-term yields fall and the yield curve inverts (shown below). In every case where 10-year yields have fallen below 3-month yields since 1955, a U.S. recession has followed in the next two years (Source, St. Louis Fed here).

Final Thoughts

So, are we in a recession? It depends on who you ask. J.P. Morgan released their 2023 Outlook on December 1st predicting unemployment to rise to 5%, inflation to fall slightly (also to 5%) and the economy to enter a mild recession, buffered by record consumer savings and an early recovery in key emerging markets like China (consumption comprises >70% of U.S. GDP, with exports and government spending making up the balance, so a strong consumer is key for their economy). In a recently published working paper, the Bank of Canada’s “base case” is that unemployment will rise from a record low of 4.9% in June to 6.7% in 2023, which will be sufficient to put a lid on the inflationary pressures that caused so many problems this past year. What we do know is that if central bankers continue to hike rates to combat inflation, the probability that we do enter a recessionary period by all definitions becomes much more likely.

The stock market is a leading indicator and often recovers well before the economy is in growth mode again. Waiting for a possible recession to buy low is not a prudent long-term investment strategy.

A recession is a terrible thing to waste as an investor. Highly leveraged (eg. Cineworld) and mismanaged companies (eg. FTX) tend to go bust more often during periods of higher borrowing costs and tighter lending standards, allowing stronger companies to gain market share and outperform in the long run, even if their share prices go down in the short run. We should be longing for these “Black Friday” deals in the market.

With the Holidays just around the corner let’s take this opportunity to be thankful for what we have and more importantly who we have. Recessionary periods can be tough on all of us but as my father says, “tough times don’t last, tough people do.”