Greenwood White Group

April 04, 2023

Globalization 3.0?

While the financial headlines these past few weeks have been understandably dominated by the turmoil in U.S. Regional and European Banks, a more somber and unsettling anniversary quietly passed a few weeks ago: the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Setting aside (but not diminishing) the human tragedy that has unfolded before our eyes for over the last year, our view is that this conflict will be remembered as the catalyst for the next paradigm shift in global energy and industrial policy. Moreover, the invasion has accelerated the reshaping of our current global supply chain, which has been under substantial pressure since the lockdowns of 2020 and 2021. These changes started to make their way into the financial press with increased references to de-globalization, consisting of the decoupling of U.S. and China, also known as re-shoring, near-shoring, and friend-shoring. We don’t agree with the view that this will spend the end to globalization, but rather that this is the next step in a gradual evolution over the past few decades as emerging economies like China and India have assumed a greater role in the global economy.

In our forthcoming posts, we will be discussing how we expect this next phase of globalization to play out in addition to potential winners and losers. For now, here is a summary of the more recent phases of globalization and the impact it has had on the global economy.

Globalization 1.0

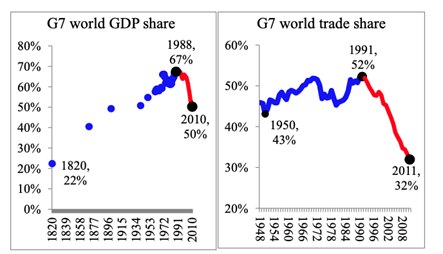

Globalization grew exponentially in the late 20th century as the internet gave way to increasingly powerful communication technology and drastically lowered the cost of moving not only goods, but ideas across the globe. This had a tremendous impact on our global economy. From 1988-2010 the G7 share of world GDP dropped from 67% to 50% and their share of trade followed suit (source: VOX EU):

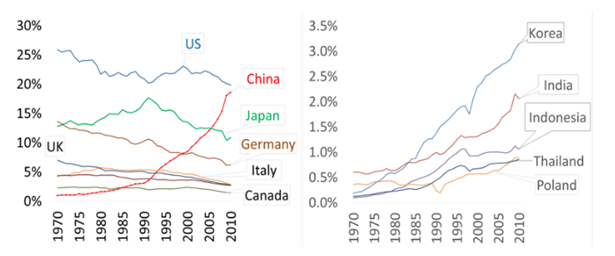

Manufacturing was hit hard and developed nations quickly moved away from producing goods on their home soil (the G7 had already been offshoring but this expedited the process). The manufacturing went to six developing nations which were coined the ‘Rapidly industrializing 6’ China, Korea, Poland, Indonesia, India, and Thailand. The table below shows how each country’s share in world manufacturing changed over this period.

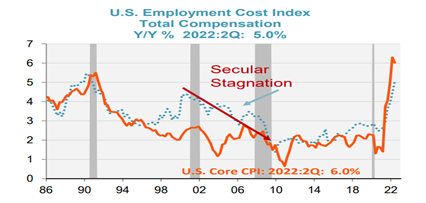

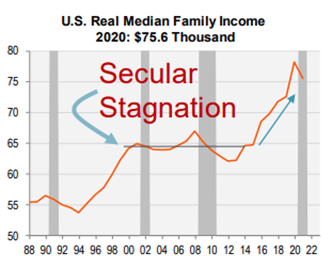

After the tech bubble popped in 2000, the U.S. entered a period of long-term (“secular”) stagnation with GDP growth sliding steadily and bottoming during the credit crisis of 2008 – 2009. Over this same period China’s GDP grew in the double-digits, on the back of massive investment in export and energy infrastructure. Capital expenditure cycles boosted productivity and employment, leading to a lost decade of household income in the U.S., with real median income stagnating from 2000 to 2015. This had the beneficial impact of keeping inflation growth very low for a long period of time, but also resulted in sustained period of below-average GDP growth for the developed nations. Sustained low inflation and a mediocre employment environment allowed for much easier monetary policy – and lower borrowing rates for a sustained period of time can have unintended consequences – with risks building in the system that need to be periodically unwound (housing bubble of 2006 – 2007).

Globalization 2.0

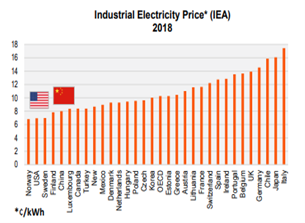

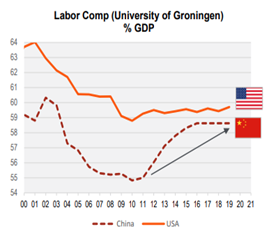

In the decade that followed the credit crisis of 2008 – 2009, China’s comparative advantages in global manufacturing gradually began to erode. Labor costs in China began to rise and converged with those in the U.S. Moreover, the U.S. experienced an energy renaissance in the U.S. from 2010 – 2015, resulting from lower costs in renewable energy production. In addition to renewable energy gains, horizontal fracking increased gas extraction which allowed the U.S. to develop a comparative advantage in electricity prices, a key input cost in manufacturing. Both are illustrated in the charts below.

Trends that reinforced the “onshoring” of manufacturing back to the U.S. included rising concerns about intellectual property theft, increasing geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and China, and the anti-corruption campaign launched by President Xi in 2012, which created regulations that stifled innovation and investment. The tariffs implemented during the Trump era at the White House (and continued by the Biden administration), as well as the supply chain interruptions during the COVID lockdowns, accelerated this trend. Consumers don’t want to see shortages in medical supplies and equipment, furniture, or auto parts again.

However, reliability comes at a cost. As jobs have returned to developed nations, so have upward wage pressures, resulting in higher prices. Inflation is often followed by rising interest rates, which reduces the overall demand for funds and helps keep prices stagnant by slowing the economy. With rising borrowing costs come rising financial risks and some unintended consequences, such as the collapse and takeover of Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and Credit Suisse in recent weeks.

In our next post, we’ll explore the options policymakers and business managers are exploring to mitigate these risks going forward.