Full Circle or Debt Spiral

Back in November 2024, we wrote a piece about how the Bank of Canada and US Federal Reserve had begun to cut their policy rates in response to moderating inflation and signs emerging of a potential slowing in the economy while market rates went in the opposite direction, highlighting the effects of this dichotomy on everyday finances, writing:

“The effect of this is that those who took out 5 year mortgages in 2020 and 2021 when rates were at all-time lows may still be facing significantly higher borrowing costs when they come to renew their mortgages in 2025 and 2026 - about 60% of all mortgages in Canada are renewing in the next 24 months.”

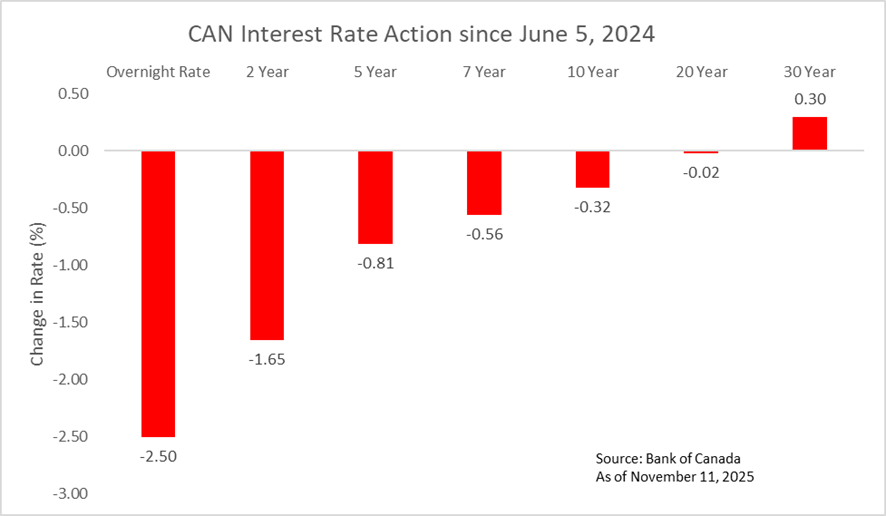

This trend has continued throughout 2025; central banks are cutting policy rates due to perceived slowing in inflation and (in Canada) slowing economic growth. However, market rates still have not taken notice. The Bank of Canada has cut its policy rate by 2.5% since it began its easing cycle on June 5th, 2024. In that time, the 5-year Government of Canada rate that underpins most mortgages, auto loans and preferred share pricing has fallen a mere 0.81%. Longer term rates have reacted with even less enthusiasm, and the 30-year bond yield has risen 0.30% in that time.

Elevated longer term rates in Canada have several knock-on effects. The biggest one is that borrowing costs for things that Canadians actually use will remain higher. Fixed mortgage rates remain elevated and roughly 60% of Canada’s fixed rate mortgages come up for renewal over the next 18 months. Auto loan rates also remain elevated, as do ‘buy now, pay later’ services for home furnishings etc.

The secondary effect is that if more people cannot afford to refinance their mortgage at higher rates, they may be forced to sell their home. This influx of homes for sale will continue to put downward pressure on residential real estate assets - a trend we have been following since prices peaked in February 2022.

There are two main policy levers to help guide an economy: monetary policy and fiscal policy. Monetary policy is controlled by the Bank of Canada in their interest rate making decisions; when the economy is slowing, they will cut rates. When the economy is rising, they will raise rates to cool expansion. By contrast, fiscal policy revolves around the spending decisions of the various levels of government: when the economy is slowing, spending will increase to stimulate growth, and conversely when the economy is expanding, spending should slow to balance the books and retool for the next downturn. This is at least how things worked for the first 150 years of our country’s history. Practically speaking, governments have become a little too spend happy in the last decade or so, often running expensive stimulus programs when there was arguably no reason to. In the most recent Bank of Canada policy decision (a rate cut to their target for the overnight rate) the Governing Council effectively waved the white flag on using monetary policy as a tool to revamp the Canadian economy, saying:

“The Canadian economy faces a difficult transition. The structural damage caused by the trade conflict reduces the capacity of the economy and adds costs. This limits the role that monetary policy can play to boost demand while maintaining low inflation.”

This would seemingly shift the onus onto the government to use their fiscal policy tools to boost economic prospects. The issue faced by the Canadian government is that the budget has not been balanced since 2015 despite strong economic tailwinds through most of that period so today the treasury does not have the war chest to flex its fiscal muscle. The most recent federal budget attempted to provide a future plan for economic stimulus and time will tell if it is effective, but the headline figure that many took away was the $78.3B deficit. As the budget did not announce any new revenue sources, this will presumably be financed with more Federal debt.

Debt financing in itself is not a bad thing, but the Canadian national debt clock now reads approximately $1.5 Trillion, or about $36,000 per Canadian citizen. The cost to service that debt is rapidly closing in on the single biggest line item in the budget, this year clocking in at $55.6 Billion dollars. For perspective that’s almost the same as the Federal government spends on healthcare transfers to provinces. It’s worth mentioning here that Canada is a bit unique in the world as our provinces have significant debts as well (this is called sub-sovereign debt).

As interest rates remain persistently high, the interest that the Canadian government has to pay to service our debt will remain higher as well. Continually financing spending with debt issuance will increase the supply of Canadian government debt in the market, putting upward pressure on its rates again - creating a vicious cycle of higher interest costs and higher debt burdens. This could continue to put pressure on real estate markets, auto markets and personal credit markets, as well as force corporations to pay more for their borrowing, costs they will pass on to consumers – this is inflationary.

We remain focused on investing our equity allocations in quality companies that have not over leveraged themselves or stretched their finances as we head into a potentially turbulent period in the economy.